In principle the eye is very similar in design to a camera. When you look at an object the light from the object passes through your pupil and is focused by the natural lens in your eye onto the retina, in exactly the same way as a camera lens focuses light onto a film in a camera.

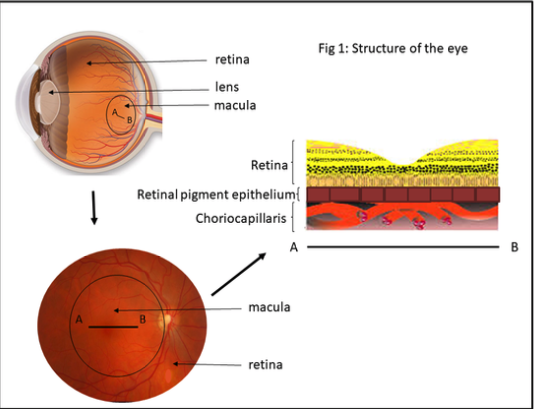

The retina has two essential parts, the peripheral retina responsible for night vision and side vision and the macula, responsible for fine vision i.e. looking at a car number plate in the distance and reading close-up. The macula is very small, only the size of a pinhead, but is critical for your fine vision. It is very important for a person to have a good macular function in at least one eye so that they can carry on fine tasks and remain independent.

When you look at an object, the light from the object hits the retina as described above and triggers a chemical reaction. The chemical reaction in turn fires off a nerve impulse that goes to your brain and creates the picture that you see. The chemical reaction, therefore, occurs millions of times a second all through your whole life, whenever you look at something. This reaction makes a waste product and normally this waste product would be recycled and reused.

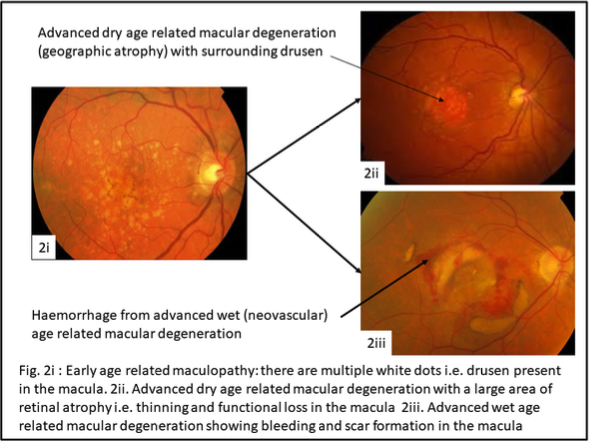

If one looks at the retinal structure in detail, the retina has two important layers beneath it i.e. deeper in the wall of the eye. The first layer is the retinal pigment epithelium as described above. This has many functions, in particular it transfers oxygen from the third layer below it, a blood vessel layer called the choriocapillaris, through it into the retina and removes waste products from the retina. In time, in patients with age-related maculopathy, the number of drusen in the retinal pigment epithelium gradually increases. This process may last for many years and happens only gradually. During this time a person’s vision typically remains good, although they may notice subtle problems, for instance difficulty reading in low light, glare in bright sunlight and reduced contrast such as an inability to distinguish different shades of grey. Nevertheless, patients with age-related maculopathy generally manage very well unless advanced age-related macular degeneration develops.

It is an eye disease which is the leading cause of severe, permanent vision loss in people over 50 to 60 years of age.

It occurs when the small central portion of the retina (the macula) wears down. The retina is the light-sensing nerve tissue at the back of the eye.

This occurs in two forms. The first occurs if the deposition of drusen in the retinal pigment epithelium becomes so great that this layer can no longer transfer oxygen and key nutrients through to the retina. The end result of this is that the retina cannot function without these and it therefore fails and thins down or becomes ‘atrophic’. This is known as advanced dry age-related macular degeneration (or ‘geographic atrophy’). The second type of advanced macular degeneration is wet (or ‘neovascular’) age-related macular degeneration. This occurs when the accumulation of drusen or debris in the retinal pigment epithelium causes cracks or breaks in its integrity to occur. Blood vessels that are normally contained in the choriocapillaris will then grow through the breaks or cracks to lie immediately beneath the retina and cause bleeding and leakage of fluid. Without treatment this process will increase in size and cause leakage of fluid, bleeding and loss of central vision – which can occur suddenly.

Talk with Prof. Michel if you have any of these symptoms right away here.

A routine eye examination and retinal imaging can identify signs of age-related macular degeneration. One of the most common early signs is drusen; tiny yellow spots under your retina or pigment clumping.

Several years ago, very large prospective clinical trials conducted in the United States showed a benefit to a particular vitamin combination called the AREDS 2 formulation in reducing the chance of advanced age-related macular degeneration occurring in patients with significant drusen under the retina or those who had drusen under the retina in one eye and advanced wet or dry age-related macular degeneration in the second eye. The vitamin combination reduced the risk of developing advanced age-related macular degeneration by about 20 to 25%, so although the vitamins may not prevent it, they do reduce the risk.

It is also advisable to stop smoking if you are a smoker as this is a further risk factor, to wear dark glasses in periods of prolonged sunlight, and to eat a regular diet rich in green vegetables to obtain the natural ingredients known to help retinal health and function.

To date there is no proven effective treatment for advanced dry age-related macular degeneration. Several studies have been conducted recently to try to prevent progression of advanced dry age-related macular degeneration by suppressing inflammation under the retina. Whilst there was great anticipation that these studies would be effective, surprisingly the results were negative and so the search continues for an effective treatment for this subtype of advanced age-related macular degeneration.

A number of large clinical trials conducted several years ago showed the benefit of anti-VEGF therapy with either Eylea (Aflibercept), Lucentis (Ranibizumab) or Avastin (bevacizumab) to prevent the progression of advanced wet age-related macular degeneration. Provided that patients continue with the treatment on a regular basis it was effective in stabilising the condition in 95% of patients and improving visual acuity by three lines on a visual acuity chart in approximately 30 to 35% of patients.

On average patients required 12 to 13 injections over a two-year period and probably at least 66% of patients need to continue treatment after two years. There are patients now who have had treatment for at least 10 years and despite many injections, sometimes to both eyes, maintain excellent vision such that they are still reading and driving without difficulty.

There are potential side-effects to the treatment, the most important of which is a 1 in 1000 risk of infection in the eye with each injection, which could significantly affect vision or even lead to complete loss of vision if it did occur. Whilst this is therefore a very unlikely event, please follow carefully the instructions given to you when beginning treatment and please see the advice sheet ‘Intravitreal injection’[M1] . This gives specific instructions on looking out for any signs of infection in the eye and what to do if you think this may have occurred.

From a practical point of view, a number of studies have compared Lucentis with Avastin, and showed that they were of similar benefit, with no difference in side-effect profile. Additional studies have shown the benefit of Eylea and Lucentis to be the same. Eylea and Lucentis are licensed treatments, and Avastin is an off-label alternative treatment which appears to be equally effective but significantly less expensive. Also, advanced dry age-related macular degeneration can occur coincidentally in patients undergoing anti-VEGF therapy for advanced wet age-related macular degeneration, and it is unclear at this time whether the anti-VEGF therapy in any way contributes to this.

It is likely in the next 5 years that the three medications above may be replaced by longer acting and novel treatments. One drug, Brolucizumab, has been recently approved, but there are current uncertainties about its safety profile. Studies to date show that in at least 50% of patients it needs to be given only every 3 months after 3 initial loading doses 1 month apart. In addition, a depot preparation is currently undergoing clinical trial testing whereby at the start of treatment a minor operation is performed on the eye during which a small reservoir device is inserted into the back of the eye that slowly releases anti-VEGF therapy into the eye. This device typically works for 15 months before requiring refill, which is a very simple 5 minute outpatient procedure similar but easier than having a regular anti-VEGF injection. Finally, there is an eye drop, given once a day and currently undergoing clinical trials that is designed to replace anti-VEGF injections into the eye altogether.

Prof. Michel is currently performing the injections at The London Medical in a dedicated intraocular injection room on Mondays all day and Thursdays from 2pm onwards. Please arrive 30 minutes before your injection time. A nurse will measure your visual acuity, intraocular pressure and insert pupil dilating drops and likely perform an OCT scan, i.e. high-resolution 3D image of the centre of the retina, the macula. Prof. Michel will see you immediately before the injection, administer anaesthetic drops, check clinical findings and answer questions etc.

The injection itself involves you lying down on a couch in the dedicated injection room for ten minutes. During this time, Prof. Michel will scrub up, put on sterile gloves and gown, sterilise around the eye with a solution of iodine, and perform the injection – which takes less than 5 seconds and which you will hardly notice. You may be aware of a light being shone into the eye at the end of the procedure, which is done to check inside the eye.

After each injection, the eye will be a little tender for a few hours, and you may experience a few floaters, and occasionally a small bubble at the bottom of your visual field in the injected eye.

These are expected and typically settle over 24 hours. Antibiotic drops are not routinely given after injection as evidence suggests they may slightly increase the risk of infection in the eye. You will, however, be given lubricant drops in case the eye feels dry or irritable post-injection. Prof. Michel or his secretary will contact you approximately three days after the procedure to check that everything has settled well and that you have no untoward symptoms.

If you note the onset, often quite rapidly, of blurred vision, increasing redness, pain or light sensitivity in the injected eye, at any time after the injection, but particularly in the first 72 hours, please make contact immediately.

The main risk of the treatment is approximately 1 in 1000 risk of infection in the eye with each injection which could significantly affect vision or even lead to complete loss of vision if it did occur. Whilst this is, therefore, a very unlikely event, please follow carefully the instructions given to you when beginning treatment and please see the advice sheet ‘Intravitreal injection’[M2] . This gives specific instructions on looking out for any signs of infection in the eye and what to do if you think this may have occurred.

Your message has been sent. We will get back to you.